On March 11, 2011, there was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake about 40 miles east of Japan. The earthquake set off a chain reaction including a tsunami and what became known as the Fukushima disaster. As a result of the Fukushima disaster, many chip fabrication facilities located in Japan went offline. Even after the disaster was contained and life continued, many of those chip fabrication facilities did not continue to manufacture the older chipsets. Instead, they chose to focus on producing the next generation chips rather than retool and continue making the old ones.

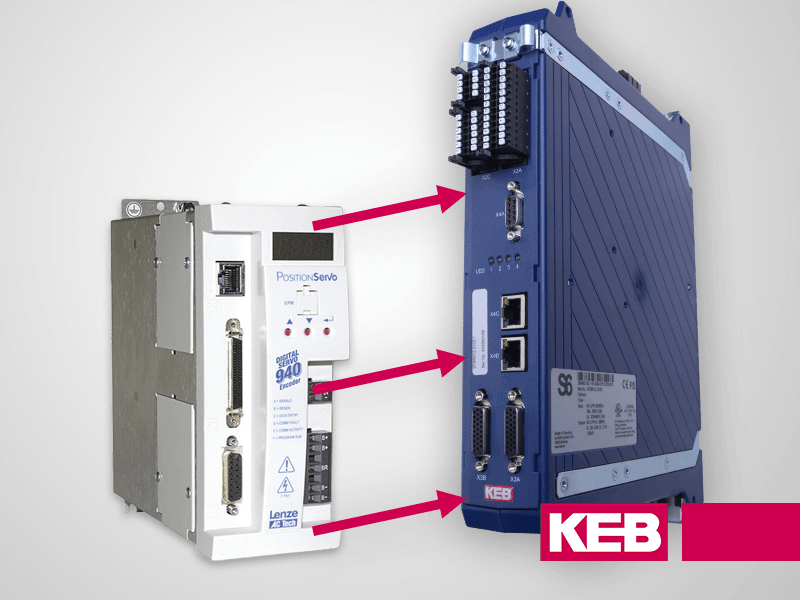

Very abruptly, this sequence of events spelled the end of KEB’s F4 inverter product. The F4 was in production/service for nearly 20 years before it was replaced by the F5 model. This is good in the electronics world. But outside of some limited parts stock, the product was no longer repairable because we did not have access to integrated circuits used on our control boards. I assure you, KEB was not the only company affected in this way by the disaster.

This brings up an interesting topic and the focus of this post – how long will my industrial automation components be manufactured and supported before they are obsolete? This is an often overlooked aspect of vendor selection – namely, choosing vendors that plan for long product lifecycles and support OEM customers for many years.

…an often overlooked aspect…[is] choosing vendors that plan for long product lifecycles and support OEM customers for many years.

The Cost of Obsolescence

Obsolescence is a major hidden risk when selecting automation components. The engineering time that is required to design and validate systems is very expensive. So a premature “redesign” shortly after a product launch carries both an opportunity expense and a capital investment expense. A Band-Aid fix that is not thoroughly vetted can underperform and be unsafe.

Components that are mechanical in nature are relatively easy to repair or replace. Motors can be rewound. Bearings can be replaced. Gears can be recut and adapter plates machined. However, integrated circuits (ICs), memory and microprocessors found in inverters, PLCs, and HMIs are much more difficult to replace. Sometimes used or overstocked parts can be found online from sites like eBay or Alibaba. But the quality and longevity of the electronic parts are dubious. The option to swap out ICs for different models or brands is often not even an option, especially for small volumes. Chipset dimensions, voltage levels, heat dissipation, and source code are a few obstacles that come to mind.

The Shiny New Model

There exists a pocket in the market of automation companies whose product is somewhere between industrial and commercial grade. Industrial because when the product is released it is a viable functioning product. The listed manufacturer performance specs are great, maybe the best on the market. And they are sold at a very competitive price. Sounds like a great value and a no-brainer.

Customers tell us they have to ‘redesign’ the machine because the 2 year old PLC/HMI they purchased is no longer available and there is no viable alternative. This is crazy and would be incredibly frustrating.

But one year later, that same PLC or HMI model has been replaced by a newer model using even newer chipsets. The drawback to this approach becomes supporting the older components in the field. Almost always, the burden to redesign to accommodate the obsoletion falls onto the OEM or the end-user. We have had customers tell us they have to “redesign” the machine because the 2-year-old PLC they purchased is no longer available and there is no viable alternative. This is crazy and would be incredibly frustrating.

Buying decisions

It is difficult to make decisions now while thinking 10 or 15 years in the future. I speak from experience as someone who has purchased consumer electronics. The product price, chip manufacturer, and performance specs like clock speed are openly listed and very easy to compare. With the rapid technological advances in consumer electronics, we have been trained to quickly compare these specs and rank options.

Longevity and support are often times more valuable than computing Horsepower.

But businesses do not (or should not) make decisions like consumers make decisions. End users make capital investment decisions to buy machinery and they expect the machinery to easily run for 10 years, 20 years, and even longer. Longevity and support are oftentimes more valuable than performance. Therefore, they should value machine designs and components that have long expected supported lifetimes.

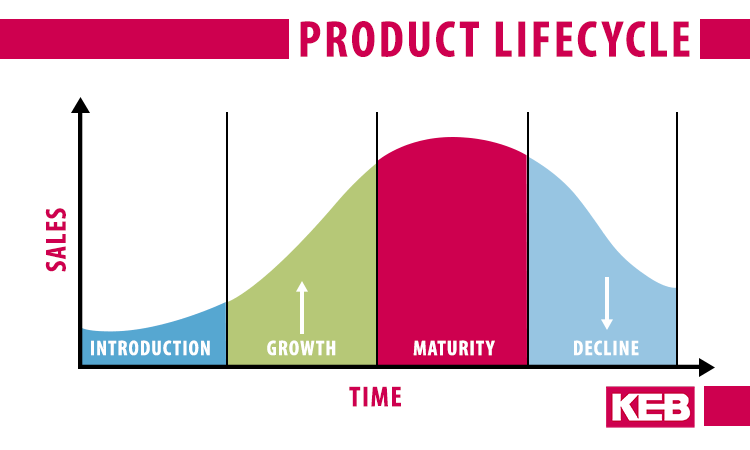

Product Lifecycles

Companies do not always publish charts like this but hopefully, their R&D and engineering teams make decisions to support a target product lifecycle. A product will go through various phases in its life. Most of its life will be in the Production phase where it is inactive production. Eventually, it will be phased out in favor of a newer model. But even after production has ended, the product must continue to be supported and repaired – especially if the product is used in critical applications.

…the product must continue to be supported and repaired – especially if the product is used in critical applications.

I had a customer ask me once to supply an “official letter” guaranteeing that my product would be supported for 25 years. This was impossible to guarantee. Not because I didn’t want to or KEB wasn’t committed to supporting the product. Rather, because there were a number of things outside of our control that affects end-of-life. One factor is that our product is made up of components and we are dependent on that company’s decisions. Another factor is exemplified by the Fukushima disaster. Events that are outside a person’s control can occur abruptly and without any opportunity to plan for them.

KEB Approach

In general, KEB strives to design products for at least a 10-20 year lifecycle. The actual lifecycle of some products might end up being more. For example, the F5 inverter is still in active production and that product is around 25 years old although it has had a couple of facelifts throughout the years.

“Selecting components for longevity early in the design process has a large impact on lifetime.”

The actual lifetime varies by product and usually ends up being determined by the IC and component manufacturers. Companies like Intel and ARM have many different chips but they select a few models that guarantee an extended lifetime and support. This allows manufacturers of industrial equipment to ensure their product will be supported for a minimum number of years. Selecting components for longevity early in the design process has a large impact on lifetime. Other features like using a SSD for memory can also work to extend the operating lifetime.

Obsolescence can be delayed but never avoided altogether. For sure, customers should receive notice when a product has entered a “legacy” or “mature” stage. This is when the product is no longer being actively produced or developed but still supported for replacements and repairs. This is the time that the user should begin to proactively develop a plan for upgrading. So if a product is abruptly obsolete, a viable alternative can quickly be implemented. Additionally, customers should be notified of a “last-time buy” opportunity where they can strategically purchase parts to support their transition plan.

Summary

Engineering redesigns are time-consuming and costly. But component obsolescence will occur and cannot be avoided entirely. However, manufacturers of automation products can lessen the blow by designing for a long product lifecycle and giving adequate notice before obsoletion. When making a buying decision, it is not only about the performance and price. Make sure to ask your supplier how long the product will be supported and where it is in its product lifecycle.

Let's Work Together

Connect with us today to learn more about our industrial automation solutions—and how to commission them for your application.